Microplastics have emerged as a pervasive environmental contaminant, infiltrating diverse ecosystems and entering the food chain. Their persistence and potential impact on both environmental and human health are raising concerns among regulators, scientists and industry stakeholders.

Microplastics are particles or fibers from synthetic polymers (plastics) measuring between 1 µm and 5 mm.[i] The most common types are polyethylene (PE), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polypropylene (PP) and polyvinyl chloride (PVC). They originate either from the intentional production of small plastic components (primary microplastics) or from the fragmentation of larger plastic items (secondary microplastics). Today, these particles are ubiquitous, found in oceans, rivers, soil and even the air we breathe.

Microplastics in the food chain

Microplastics can enter the food chain through multiple pathways. Raw ingredients, production sites (e.g. pipelines, reservoirs, gaskets, filter aids), packaging materials (bottle or container materials, lids, sealings, labels, tea bags) and the surrounding air can all contribute to the contamination of food with microplastics.

In aquatic environments, fish and shellfish can ingest these particles directly, which then accumulate in the organism. In agriculture, microplastics infiltrate soils via plastic mulch films, polymer-coated fertilizers, sewage sludge and contaminated irrigation water. Crops can then absorb microplastics through their roots, which may ultimately lead to their presence in fruits, vegetables or grains consumed by humans.[ii],[iii]

Another source of contamination is animal feed. A 2023 study of livestock and poultry feeds found microplastics ranging between 2 µm and 10 µm in all tested samples. They have also been detected in meat, milk and blood from farm animals.[iv],[v] However, the sources and pathways of contamination in food and feed, and their accumulation in human and animal organisms, remain diverse and insufficiently understood, requiring further investigation.

Health impact

While acute health risks associated with consuming microplastic-contaminated food are considered low, concerns persist about the long-term effects of chronic exposure, which are still under investigation. Microplastics can act as carriers of additives (e.g. plasticizers, flame retardants, colorants) and environmental contaminants such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), heavy metals, bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).[vi] These particles have been detected in the digestive tracts of various organisms and may cause tissue inflammation and oxidative stress.[vii],[viii]

Microplastics may also act as endocrine disruptors – substances that mimic hormones and interfere with reproductive health, fetal development and metabolic processes. Animal studies also suggest that ingested microplastics may increase cancer risk, particularly in the digestive tract, and contribute to inflammation and immune system disruption.[ix]

Regulatory responses

Despite growing awareness and concerns about microplastics as a threat to food safety and public health, policy responses remain fragmented. Environmental aspects and food-related health issues are often addressed separately, limiting the effectiveness of interventions. To bridge these gaps, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) advocates for a One Health approach, integrating human, animal and environmental health perspectives. This holistic framework is crucial for understanding how microplastics move through agrifood systems and for designing effective interventions.[x]

In the European Union (EU), regulatory measures are already underway. Directive (EU) 2020/2184, which covers water quality for human consumption, has added microplastics to the official ‘watchlist’. On March 11, 2024, an analytical method for assessing microplastic content was formally integrated through Commission Delegated Decision (EU) 2024/1441. Additionally, Regulation (EU) 2023/2055 bans the intentional addition of microplastics in numerous products (e.g. cosmetics, paints, medicines, fertilizers) as part of the REACH regulation.

Tools for microplastic reduction

Testing is our most effective tool for detecting microplastics. ISO 16094-2 has standardized the analysis of microplastics in water. Packaging can be evaluated using rinsing tests to support responsible material selection and demonstrate a precautionary approach to potential microplastic release.

Analyzable polymer types: polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polycarbonate (PC), polystyrene (PS), polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polyamide (PA), polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), polyurethane (PU)

Additional materials: silicone (PDMS), nitrile polymers, polylactide (PLA), polyaryletherketone (PAEK), etc.

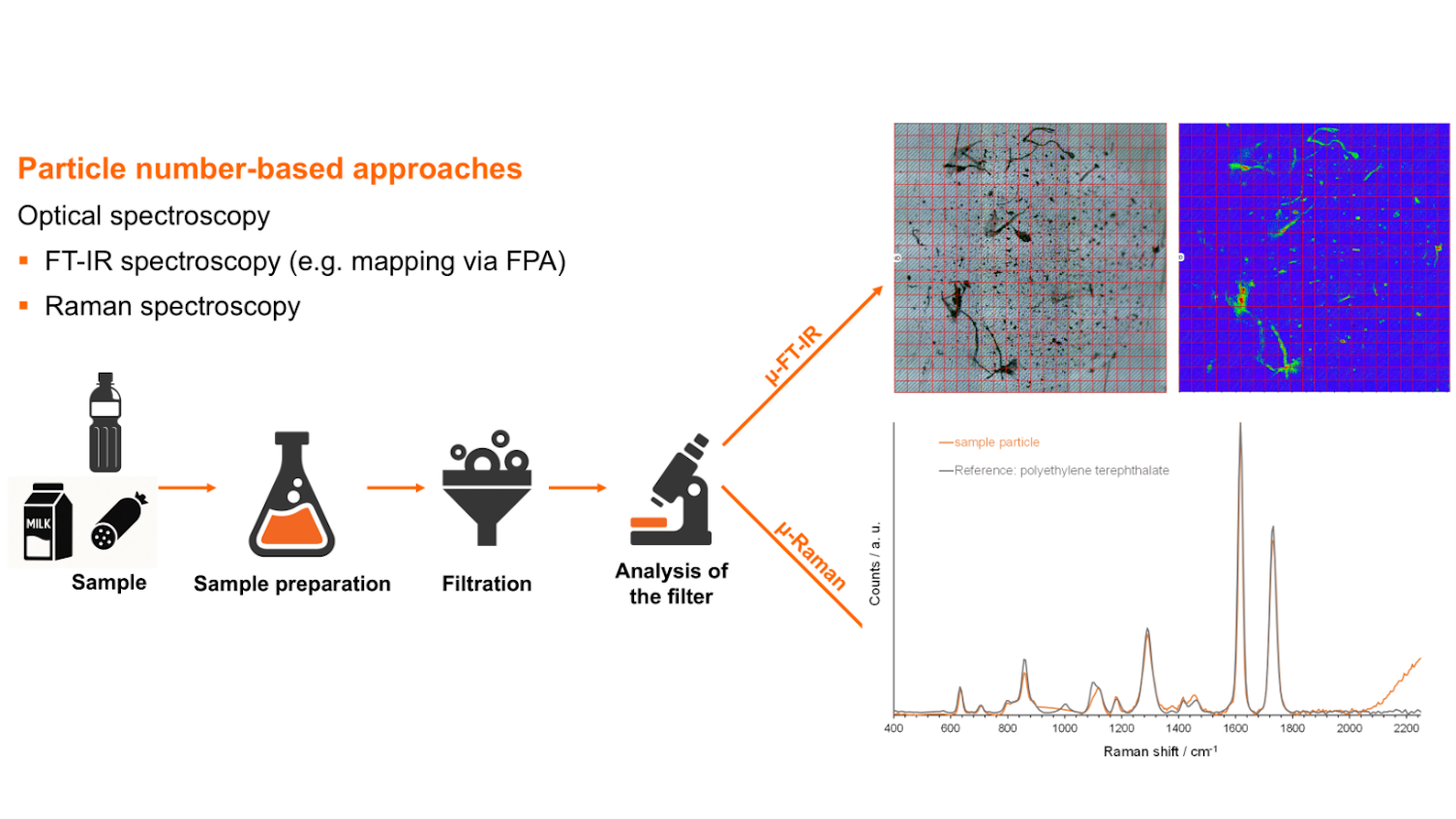

Particle number-based analytical approaches for microplastic testing in water typically employ Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy and Raman spectroscopy following sample preparation and filtration. FTIR measures the specific absorption of infrared light by the microplastic sample, whereas Raman spectroscopy measures the so-called scattering of monochromatic light usually from a laser. Both techniques enable the determination of particle count, polymer type and particle size. Using Raman spectroscopy, particles as small as 6 µm can be analyzed, while FT-IR imaging typically has a detection limit of 20 µm.

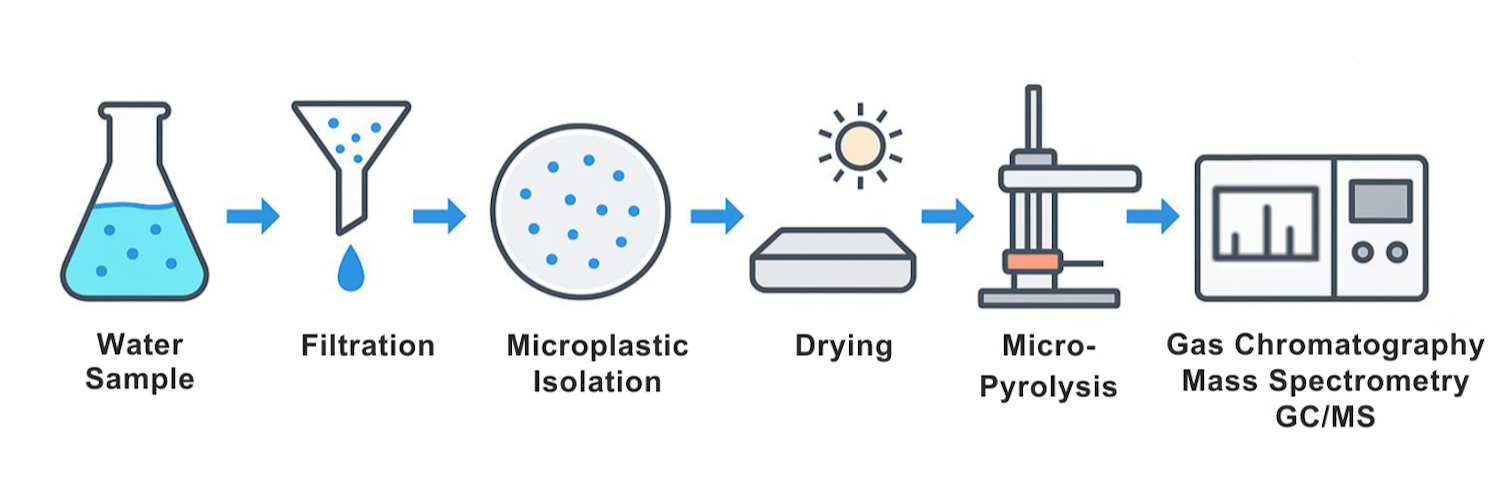

Micro-pyrolysis coupled with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS) is another powerful analytical technique for characterizing microplastics. Aqueous samples are filtered to collect microplastics.

The collected particles are dried and sometimes pre-treated to remove organic matter. The sample is placed in a micro-furnace and rapidly heated (typically 500–700 °C) in an inert atmosphere (e.g., helium). This thermal decomposition breaks polymers into smaller volatile fragments without combustion. The pyrolysis products are carried by an inert gas into the GC column where the compounds are separated based on volatility and polarity. The separated compounds are ionized and detected by MS. The resulting spectra are compared to reference libraries to identify polymers.

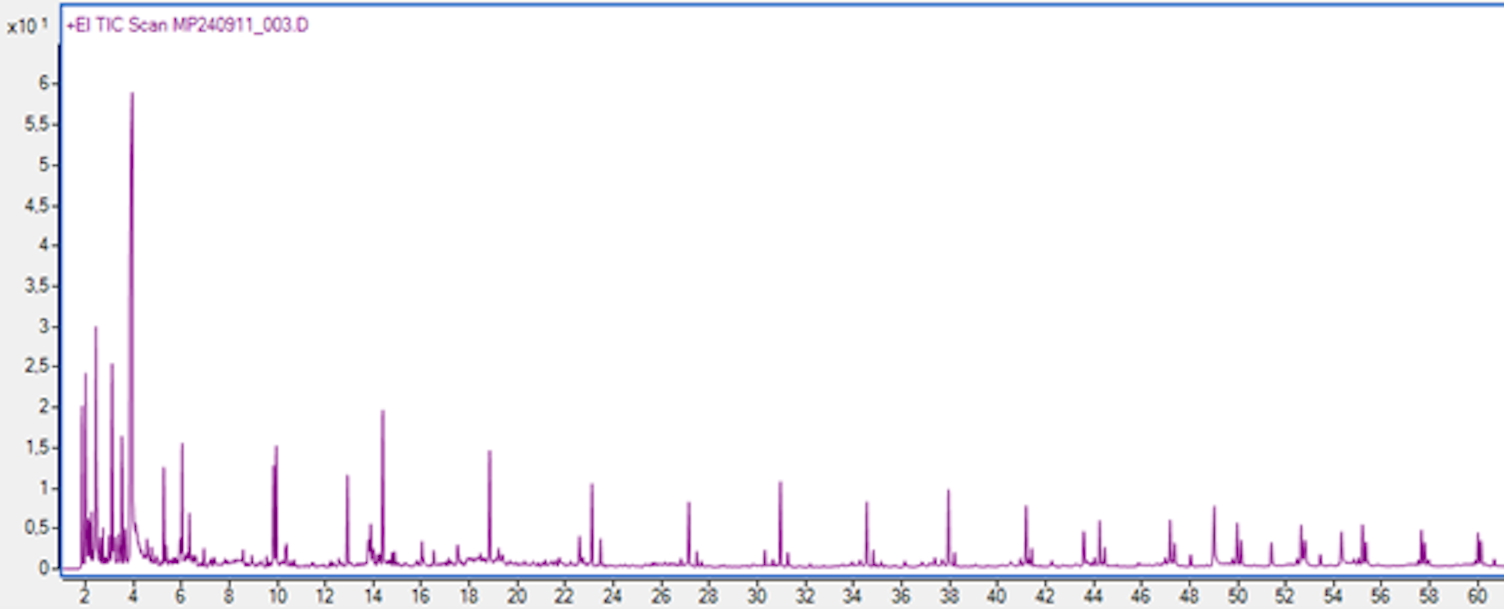

Py-GC/MS chromatogram HDPE in a sample of surface water (freshwater, recipient)

Foods with more complex matrices than water may require additional or alternative sample preparation steps depending on their composition. Common approaches include:

- Alkaline digestion

- Enzymatic digestion

- Oxidative digestion

- Density separation

SGS solutions

Our laboratories apply state-of-the-art equipment and methodologies to analyze samples for microplastic content, including particle count, size and polymer type. When no standard method exists, our experts develop sample-specific analytical approaches to ensure robust and appropriate testing.

All sample preparation and measurements are performed under cleanroom-like environmental conditions to minimize contamination from the laboratory environment. Internal quality assurance procedures and participation in interlaboratory comparisons support the reliability and consistency of the results.

IMPACT NOW for sustainability

Microplastic testing is a core service within our IMPACT NOW for sustainability initiative, which brings together solutions under four strategic pillars: Climate, Nature, ESG Assurance and Circularity. Under the Nature pillar, we offer practical solutions to detect and assess microplastics, enabling better decision-making, regulatory compliance and environmental responsibility. Our goal is to empower businesses to drive meaningful change and meet the rising demands of regulators, stakeholders and conscious consumers.

IMPACT NOW for sustainability embodies our commitment to a climate-neutral, nature-positive and pollution-free future.

[i] N. B. Hartmann et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 1039-1047

[ii] Microplastics In Agriculture: The Unseen Threat To Food Security - Sigma Earth

[iii] Toxic Harvest: How Microplastics Are Threatening Global Food Supplies - Climate Fact Checks

[v] Around 80% of cow and pig meat, blood and milk contains plastic

[vi] V. Kinigopoulou et al., J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 350, 118580.

[vii] Zantis et al., Environ. Poll. 2021, 269, 116142.

[viii] R. Qiao et al., Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 662, 246-253

[x] Plastic pollution and agrifood systems: Why One Health matters now more than ever

About SGS

SGS is the world’s leading Testing, Inspection and Certification company. We operate a network of over 2,500 laboratories and business facilities across 115 countries, supported by a team of 99,500 dedicated professionals. With over 145 years of service excellence, we combine the precision and accuracy that define Swiss companies to help organizations achieve the highest standards of quality, compliance and sustainability.

Our brand promise – when you need to be sure – underscores our commitment to trust, integrity and reliability, enabling businesses to thrive with confidence. We proudly deliver our expert services through the SGS name and trusted specialized brands, including Brightsight, Bluesign, Maine Pointe and Nutrasource.

SGS is publicly traded on the SIX Swiss Exchange under the ticker symbol SGSN (ISIN CH1256740924, Reuters SGSN.S, Bloomberg SGSN:SW).